Ocean Restoration: How Red Tape Prevents Marine Ecosystem Recovery

Last week, I read something that left me stunned. Twenty-five marine scientists from 18 countries just published urgent findings: the regulations designed to protect our oceans are actually preventing their recovery.

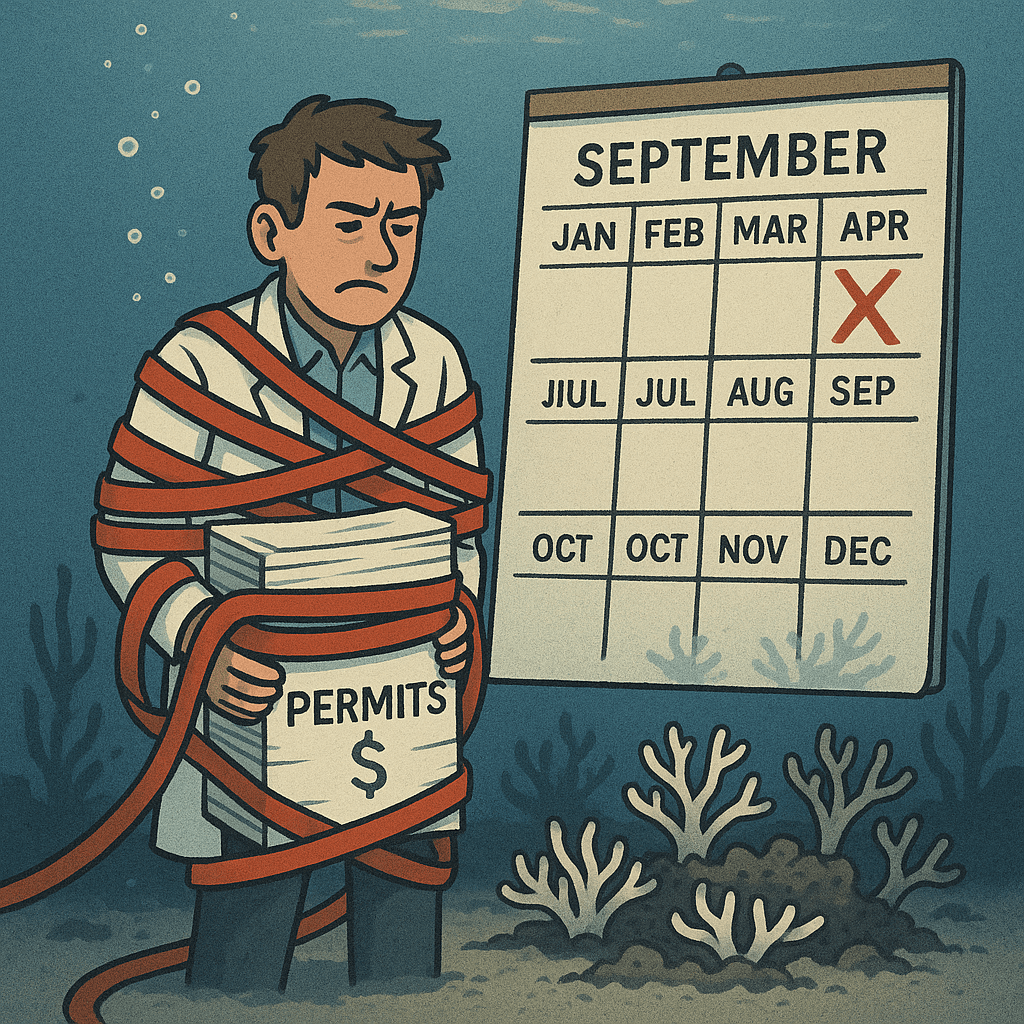

Here’s the problem: Scientists have the training, the funding, and proven restoration techniques. But government ocean restoration red tape forces them to wait 6-12 months for permits, so long that; oftentimes, the reef, seagrass meadow, or mangrove forest they wanted to save degrades beyond repair before they can even start.

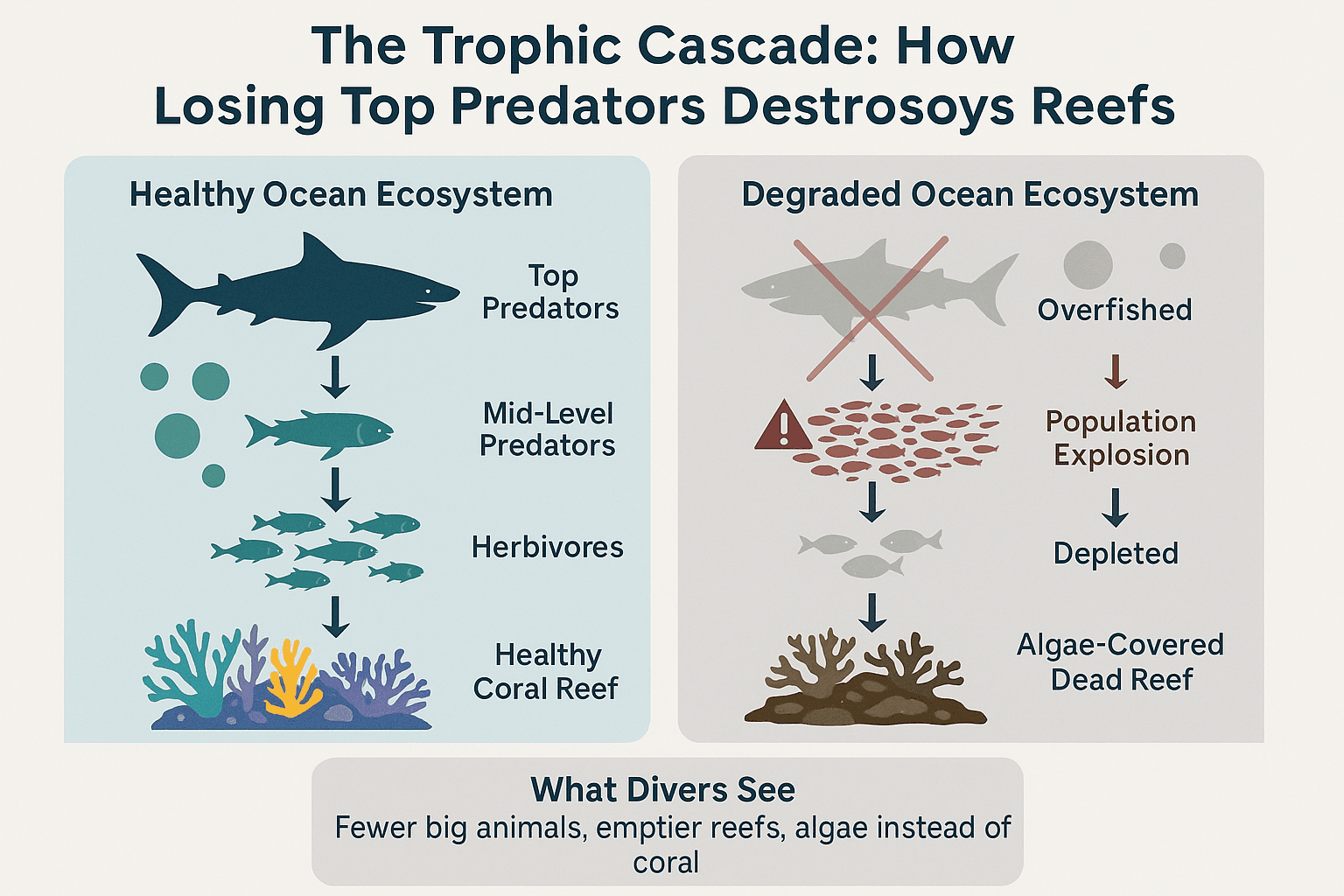

Every diver knows the heartbreak of returning to a once-vibrant reef only to find it bleached or barren. We’ve been told marine restoration is ramping up globally. But this study, published in Cell Reports Sustainability, reveals a troubling truth: bureaucratic barriers are preventing ocean restoration from happening at the scale and speed needed to meet critical 2030 targets.

For divers, this isn’t academic; it’s about whether the dive sites we cherish will exist for future generations.

The Global Ocean Restoration Crisis: Scale and Urgency

The Global Ocean Restoration Crisis: Scale and Urgency

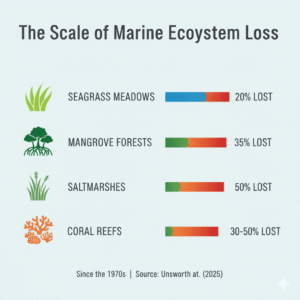

The numbers are sobering. Globally, we’ve lost at least 20% of seagrass meadows, over 35% of mangrove forests, and up to 50% of saltmarshes (Unsworth et al., 2025). Coral reefs are facing critical tipping points. Our seas are increasingly devoid of top predators, triggering a trophic cascade where mid-level predators explode in number, herbivores decline, and once-vibrant reefs transform into algae-covered wastelands.

The United Nations declared 2021 to 2030 the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework set an ambitious target: restore 30% of all degraded ecosystems by 2030.

We’re now halfway through that decade. So why isn’t marine restoration happening at scale?

The Bureaucratic Stranglehold

The research team, led by Dr. Richard K.F. Unsworth from Swansea University and Project Seagrass, surveyed restoration practitioners across six marine ecosystems. What they found was a systematic failure of regulatory frameworks to support (rather than hinder) ocean recovery efforts.

Before diving into the problems, it’s important to acknowledge something critical: marine restoration actually works. A comprehensive 2025 study in Nature Communications found that marine ecosystem restorations have an average success rate of approximately 64% (Waltham et al., 2025). That’s not experimental or theoretical. That’s real restoration producing measurable results. The problem isn’t whether restoration can work. It’s whether we’ll let it happen at the scale and speed needed.

Endless Permit Delays and Prohibitive Costs

One of the most significant barriers is the licensing process itself. Think about it this way: you’re a marine scientist who has identified the perfect window for coral restoration, maybe right after a bleaching event when competition is low, or during optimal water temperatures for seagrass planting. But then;

“licensing delays compound the problem, often taking 6 to 12 months or sometimes even longer, with multiple permits required across multiple agencies, slowing delivery, increasing costs, and reducing project scale”

-Unsworth et al., 2025, p. 5

By the time you navigate the maze of permits from multiple agencies, that window has closed. The restoration fails not because of bad science, but bad timing forced by bureaucracy.

The financial burden is equally crushing. Rising licensing costs, annual fees, and advisory charges make small-scale projects economically unfeasible while favoring large developers who often lack the appropriate restoration expertise. As the study reveals, this creates a perverse incentive structure where those with money but without ecological knowledge can proceed, while underfunded scientists with decades of experience cannot.

Scientists Locked Out of Marine Protected Areas

Perhaps most frustratingly for restoration scientists, they’re often prohibited from working in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are the very places where restoration would be most effective. The study documents how restoration efforts in Australia have been

“limited deployments inside MPAs in Sydney, forcing most work over the past decade into unprotected areas where conditions may be less advantageous for restoration”

-Unsworth et al., 2025, p. 4

This creates an absurd catch-22: MPAs are protected because they contain sensitive habitats or species, but degraded areas within those MPAs can’t be restored because, well, they’re protected. Meanwhile, scientists are forced to work in unprotected areas where their restoration efforts may be undermined by ongoing fishing, development, or other disturbances.

[amazon box=”0393355551″]

Regulatory Confusion & Contradictions Across Multiple Agencies

The regulatory landscape is often so complex and contradictory that even well-intentioned practitioners can’t navigate it. In the Philippines, which has relatively high numbers of coral restoration projects, researchers found that “seventeen policies relate to coral restoration, three of which address restoration techniques. These are inconsistent: one requires national permits, another requires local permits, and a third only provides technical guidance” (Unsworth et al., 2025, p. 6).

Limited technical expertise within regulatory agencies—particularly at local levels—further compounds the problem. Restoration practitioners often know more about marine ecology than the regulators evaluating their permits, yet must wait months for approvals that may be based on outdated scientific understanding.

Innovation Stifled by Outdated Permitting Rules

Climate change is rapidly altering ocean conditions, meaning restoration approaches that worked a decade ago may not work today. Scientists increasingly need to test innovative techniques like assisted gene flow (moving genetic material between populations to increase resilience), assisted migration (moving species to new areas as their habitat shifts), or even working with established non-native species that provide ecosystem services.

Yet regulations often prevent these approaches entirely. The authors argue that “species movements that facilitate gene flow or regulate seed collection lack a scientific basis, hindering restoration by preventing collection from suitable donor sites” (Unsworth et al., 2025, p. 6). In some cases, licensing authorities dictate which donor populations must be used without considering whether they’re environmentally compatible with the restoration site, which undermines the entire effort.

Marine Restoration Permitting: Where the Barriers Hit Hardest

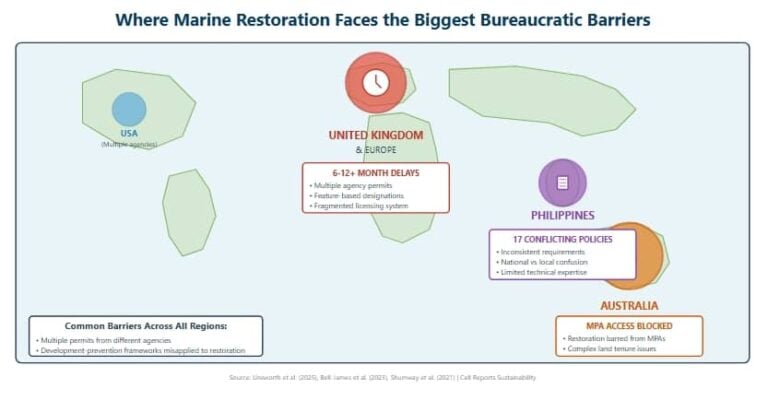

While regulatory challenges plague marine restoration globally, certain regions face particularly severe bottlenecks:

United Kingdom and European Union Restoration Barriers

The UK exemplifies the bureaucratic maze. Marine licensing and feature-based designations fail to account for ecological connectivity, which is essential for ecosystem recovery (Bell-James et al., 2023). England’s seagrass restoration projects face 6 to 12-month delays (or longer) with permits required from multiple agencies. The push for a “one-stop-shop” licensing approach reveals just how fragmented the current system is. Across the broader EU, the need for continent-wide legal reform through the Nature Restoration Regulation underscores the inadequacy of existing frameworks.

Australia’s Marine Restoration Regulatory Maze

Despite being a world leader in marine protection, Australia lags significantly in restoration implementation. Marine restoration projects have yet to be undertaken on a large scale, hampered by complex permitting across Queensland, New South Wales, and other jurisdictions (Shumway et al., 2021). Land tenure issues create additional legal tangles. Sydney’s successful Operation Crayweed project (see below), for instance, was forced to work outside Marine Protected Areas due to permitting restrictions, resulting in restoration occurring in suboptimal locations.

The Philippines’ Contradictory Coral Restoration Policies

Coral restoration faces a regulatory nightmare of contradictory policies. Seventeen different policies relate to coral restoration, with three addressing restoration techniques but providing inconsistent guidance. One requires national permits, another demands local permits, and a third offers only technical guidance with no clear approval pathway (Unsworth et al., 2025). Limited technical expertise at local regulatory levels compounds the confusion, leaving practitioners uncertain about requirements.

United States Ocean Restoration Challenges

Based on my research, there is far less specific detail about US permitting delays than there is for the UK, Australia, and the Philippines. However, here’s what I found:

The Florida Keys:

-

- The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary has extensive restoration programs (Mission: Iconic Reefs)

- Multiple federal agencies involved: NOAA, EPA, Army Corps of Engineers, Fish & Wildlife Service

- The “Restoration Blueprint” process began in 2011, suggesting long-term bureaucratic processes

- EPA and the State of Florida have been working with Monroe County for over fifteen years to eliminate onsite septic systems U.S. Coral Reefs | US EPA, showing decade-long regulatory timelines

California:

-

- The study specifically examined California restoration projects

- Point Reyes and other California MPAs have Marine Life Protection Act regulations

Hawaii:

-

- Multiple restoration initiatives documented

- Federal, state, and territorial coordination required

- Ridge to Reef Initiative involves multiple agencies

US Virgin Islands & Puerto Rico:

-

- Part of the US Coral Reef Task Force jurisdiction

- Multiple overlapping federal and territorial authorities

The US Permitting Challenge:

The US has a “multi-level agency” problem rather than single-location delays:

- Clean Water Act Section 404 permits (Army Corps of Engineers)

- Endangered Species Act consultation (Fish & Wildlife Service)

- National Marine Sanctuary regulations (NOAA)

- State-level permits

- Sometimes tribal consultation requirements

[amazon table=”1611″]

USA Based Divers, Contact Your Representatives

Our Voice Matters: The Power of the Diving Community

We are not powerless bystanders in this crisis. The global scuba diving community represents a $20.4 billion economic force, supporting 124,000 jobs across 170 countries and advancing sustainable development in coastal communities worldwide, as detailed in our previous coverage of the “Scuba Diving Economy’s Remarkable $20.4B Annual Impact.” When we speak (in unison), governments and policymakers will listen. Because we’re not just passionate advocates for ocean health, we’re the economic backbone of countless coastal towns and marine conservation programs.

But our power extends far beyond dollars. We are the eyes beneath the surface. We witness firsthand what scientists are fighting to restore and what bureaucrats are unknowingly blocking. Every degraded reef we photograph, every bleached coral we document, every empty dive site we reluctantly cross off our bucket lists—these are our stories to tell.

When 80% of dive jobs are filled by local residents in the communities where we travel, we’re creating a global network of ocean advocates. When we share this article, contact our representatives, and demand streamlined restoration permitting, we’re not just supporting marine scientists—we’re fighting for the future of our sport, our livelihoods, and the underwater world we love. The question isn’t whether marine restoration can work. It’s whether we’ll raise our voices loud enough to let it happen.

Key Senate Committees & Members

Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

Oversees NOAA, which manages marine sanctuaries and coral restoration

- Chair: Ted Cruz (R-TX)

- Ranking Member: Maria Cantwell (D-WA)

- Key Members with Coastal States:

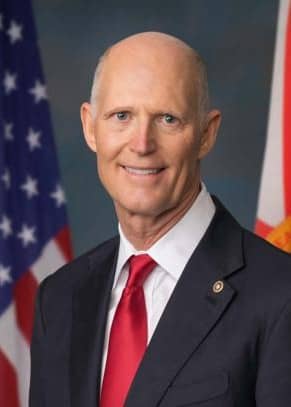

- Rick Scott (R-FL) – Florida Keys restoration

- Marco Rubio (R-FL) – Florida Keys restoration

- Brian Schatz (D-HI) – Hawaii coral reefs

- Mazie Hirono (D-HI) – Hawaii coral reefs

- Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) – Great Lakes coastal issues

Senate Environment and Public Works Committee

Oversees EPA, Clean Water Act

- Chair: Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV)

- Ranking Member: Tom Carper (D-DE)

- Coastal Members:

- Jeff Merkley (D-OR)

- Ed Markey (D-MA)

Oversees NOAA, which manages marine sanctuaries and coral restoration

- Chair: Ted Cruz (R-TX)

- Ranking Member: Maria Cantwell (D-WA)

- Key Members with Coastal States:

- Rick Scott (R-FL) – Florida Keys restoration

- Marco Rubio (R-FL) – Florida Keys restoration

- Brian Schatz (D-HI) – Hawaii coral reefs

- Mazie Hirono (D-HI) – Hawaii coral reefs

- Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) – Great Lakes coastal issues

Oversees EPA, Clean Water Act

- Chair: Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV)

- Ranking Member: Tom Carper (D-DE)

- Coastal Members:

- Jeff Merkley (D-OR)

- Ed Markey (D-MA)

Key House Committees & Members

House Natural Resources Committee

Oversees the National Park Service, marine protected areas

- Chair: Bruce Westerman (R-AR)

- Ranking Member: Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ)

- Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife and Fisheries:

- Jared Huffman (D-CA) – California coast, very active on marine issues

- Cliff Bentz (R-OR) – Oregon coast

House Science, Space, and Technology Committee

Oversees NOAA research

- Chair: Frank Lucas (R-OK)

- Ranking Member: Zoe Lofgren (D-CA)

Garmin vs. Shearwater vs. Suunto for PPO2 tracking

Oversees the National Park Service, marine protected areas

- Chair: Bruce Westerman (R-AR)

- Ranking Member: Raúl Grijalva (D-AZ)

- Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife and Fisheries:

- Jared Huffman (D-CA) – California coast, very active on marine issues

- Cliff Bentz (R-OR) – Oregon coast

Oversees NOAA research

- Chair: Frank Lucas (R-OK)

- Ranking Member: Zoe Lofgren (D-CA)

Garmin vs. Shearwater vs. Suunto for PPO2 tracking

Geographic Representatives

Florida (Most Critical – Florida Keys restoration)

Senate:

- Rick Scott (R)

- Marco Rubio (R)

House:

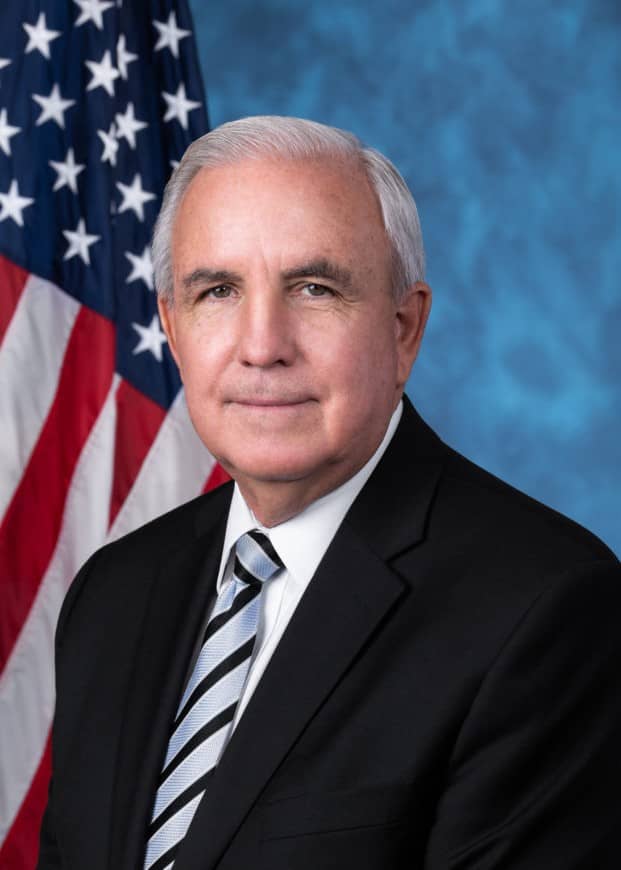

- Carlos Gimenez (R-FL-28) – Miami/Keys area

- Mario Díaz-Balart (R-FL-26) – South Florida

- María Elvira Salazar (R-FL-27) – Miami

Hawaii (Major Coral Reef Jurisdiction)

Senate:

- Brian Schatz (D)

- Mazie Hirono (D)

House:

- Ed Case (D-HI-1)

- Jill Tokuda (D-HI-2)

Garmin vs. Shearwater vs. Suunto for PPO2 tracking

California (Case Study Location)

Senate:

- Alex Padilla (D)

- Adam Schiff (D)

House:

- Jared Huffman (D-CA-2) – TOP PRIORITY – very active on ocean issues, sits on Natural Resources Committee

- Mike Thompson (D-CA-4) – North Coast

- Salud Carbajal (D-CA-24) – Central Coast

- Mike Levin (D-CA-49) – San Diego coast

Virgin Islands & Puerto Rico

House Delegates (non-voting but influential):

- Stacey Plaskett (D-VI)

- Jenniffer González-Colón (R-PR)

Senate:

- Rick Scott (R)

- Marco Rubio (R)

House:

- Carlos Gimenez (R-FL-28) – Miami/Keys area

- Mario Díaz-Balart (R-FL-26) – South Florida

- María Elvira Salazar (R-FL-27) – Miami

Senate:

- Brian Schatz (D)

- Mazie Hirono (D)

House:

- Ed Case (D-HI-1)

- Jill Tokuda (D-HI-2)

Garmin vs. Shearwater vs. Suunto for PPO2 tracking

Senate:

- Alex Padilla (D)

- Adam Schiff (D)

House:

- Jared Huffman (D-CA-2) – TOP PRIORITY – very active on ocean issues, sits on Natural Resources Committee

- Mike Thompson (D-CA-4) – North Coast

- Salud Carbajal (D-CA-24) – Central Coast

- Mike Levin (D-CA-49) – San Diego coast

House Delegates (non-voting but influential):

- Stacey Plaskett (D-VI)

- Jenniffer González-Colón (R-PR)

Editor’s Top 5 Recommendations for Maximum Impact (USA):

Jared Huffman (D-CA)

Natural Resources Committee, extremely active on marine conservation, California case study location

Rick Scott (R-FL)

Senate Commerce Committee, Florida Keys is ground zero for US coral restoration

Brian Schatz (D-HI)

Senate Commerce Committee, Hawaii has major restoration programs

Maria Cantwell (D-WA)

Ranking Member, Senate Commerce (NOAA oversight)

Carlos Gimenez (R-FL)

Represents the Keys directly

For USA Divers – Action Strategy:

- If you dive in Florida Keys: Contact Scott, Rubio, Gimenez

- If you dive in Hawaii: Contact Schatz, Hirono, Case, Tokuda

- If you dive in California: Contact Huffman, Padilla, Schiff

- General ocean conservation: Contact Cantwell (Senate) and Huffman (House)

The Common Thread:

Across all these countries and ecosystems, restoration practitioners face multiple permits from different agencies (environmental, fisheries, coastal management), MPA restrictions that block access to optimal sites, and the fundamental problem of applying development-prevention frameworks to restoration activities. The regulations were designed to stop harm, not facilitate recovery, which is now hindering restoration efforts.

[amazon box=”1604271434″ template=”horizontal”]

Case Study: Operation Crayweed Succeeds Despite Regulations

Proof that restoration works: Sydney’s Underwater Forest Returns

Sydney’s coast once boasted 70 kilometers of dense crayweed forests (a type of kelp). During the 1980s, pollution caused them to vanish completely. But here’s the good news: they’re coming back.

Operation Crayweed, led by researchers from the University of New South Wales and Sydney Institute of Marine Science, has successfully reestablished crayweed at multiple Sydney sites since 2011. The transplanted forests survived at rates of 40 to 70%, grew to around 60 centimeters, and reproduced naturally, creating 5 to 12 new recruits per square meter after just one year (Campbell et al., 2014).

The project used innovative genetic mixing, sourcing populations from north and south of Sydney to reflect natural diversity. Now, after years of trial and refinement, it’s considered the most successful seaweed restoration project in Australia (Vergés et al., 2020).

The catch? As the Unsworth report documents, most of this work had to happen outside Marine Protected Areas due to permitting restrictions, forcing teams into “unprotected areas where conditions may be less advantageous for restoration” (Unsworth et al., 2025, p. 4). Imagine how much faster recovery could happen if the best sites were available.

For divers: Sydney’s restored kelp forests are now becoming dive destinations again, hosting fish, abalone, and crayfish populations. This is what’s possible when restoration is allowed to proceed, even when it’s hampered by regulations.

Operation Crayweed

Researchers, scientists and volunteers working to restore Sydney’s critically important underwater forests. Attributed to: Gardening Australia. https://youtu.be/F762n8qJoTU

Mission: Iconic Reefs

Bold action can change the trajectory of the reefs of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Attributed to NOAA Sanctuaries. https://youtu.be/iRSPU4V3ilw

What This Means for Divers

For the diving community, these bureaucratic failures have direct consequences:

- Degraded Dive Sites Stay Degraded. That bleached reef you’ve been watching decline? Restoration could help it recover, but scientists may be locked out by permit requirements or costs.

- Missed Opportunities. The best locations for restoration (often within MPAs where you dive) are frequently off-limits to restoration work, even when degradation is obvious.

- Lost Time. Every year of regulatory delay is a year of continued decline. Marine ecosystems have tipping points beyond which recovery becomes exponentially harder or impossible.

- Failed Projects. When regulations force scientists to use suboptimal sites, donor materials, or timing, restoration projects fail. This wastes limited funding and creates skepticism about whether restoration works at all.

[amazon box=”B0074VTHSY” template=”horizontal”]

What Ocean Restoration Regulations Need Change in 2025 – 6 critical reforms

The research team proposes six key improvements to regulatory frameworks:

- Embrace innovative approaches that account for climate change rather than trying to recreate historical ecosystems

- Create “innovation sandpits” where scientists can test new restoration techniques with streamlined permitting

- Establish marine restoration areas with blanket permissions for restoration activities, potentially within existing MPAs

- Require transparent reporting so the restoration community learns from both successes and failures

- Streamline licensing to reduce multiple permits and cover ecologically realistic timeframes (decades, not years)

- Eliminate licensing fees for marine restoration to remove financial barriers for non-profit conservation work

“we need to think way beyond what we see as baselines [historical or even current] and view a changing climate as a means of rethinking coastal seascapes to better support our future”

– Unsworth et al., 2025, p.

How Divers Can Advocate for Better Marine Restoration Permitting

The diving community has always been on the front lines of ocean conservation. Here’s how you can help:

Advocate for regulatory reform. Contact your representatives and marine management agencies. Share this research. Make it clear that divers support science-based restoration with streamlined permitting.

Support restoration organizations. Many restoration projects are funded by charitable donations. Your support helps offset the financial burden of licensing costs and allows scientists to continue working despite regulatory barriers.

Document and report. Your observations as divers are valuable data. Report degraded sites, successful restoration areas, and changes you observe over time.

Spread awareness. Share stories about restoration challenges and successes within the diving community and on social media.

[amazon box=”9401772487″ template=”horizontal”]

The Bottom Line

We’re in a race against time to save our oceans, but the runners are being tied up in red tape. Marine restoration works. We have the science, the techniques, and increasingly, the funding. What we don’t have is a regulatory system designed for the scale and urgency of the challenge.

“For the restoration of marine ecosystems to happen at any genuine, meaningful scale, we believe that an urgent and major cultural shift is required in how licensing and regulation of marine restoration activities are done”

-Unsworth et al., 2025, p.

The reefs, seagrass meadows, and mangrove forests we love to explore are running out of time. The scientists trying to save them need our support, and they need regulatory systems that help rather than hinder their critical work.

The question isn’t whether we can restore our oceans. It’s whether we’ll remove the barriers preventing restoration before it’s too late.

As an Amazon Associate, Scuba Insider may earn a small commission from qualifying purchases at no additional cost to the customer.

Dive Complete!

If this article sparked a memory or you’ve got advice for fellow divers, share it in a comment below. Your insight helps keep our dive community strong.

Frequently Asked Questions about Ocean Restoration Regulations

Why do ocean restoration projects need permits?

Ocean restoration permits are required to ensure projects don’t harm existing ecosystems, but current regulations were designed to prevent development, not facilitate restoration.

How long does marine restoration permitting take?

Marine restoration permitting typically takes 6-12 months, with some projects experiencing even longer delays across multiple agencies.

Can coral reef restoration work in Marine Protected Areas?

Often no. Scientists are frequently prohibited from conducting reef restoration in Marine Protected Areas despite these being the optimal locations for restoration success.

What is the success rate of marine ecosystem restoration?

Marine ecosystem restorations have an average success rate of approximately 64% when allowed to proceed without excessive delays.

How can divers help reform ocean restoration regulations?

Divers can contact their representatives, support restoration organizations, document reef conditions, and advocate for streamlined marine restoration permitting.

References

Transparency matters. Behind the toggle, you’ll find direct links to the reports, research papers, and expert sources that shaped this story. We encourage readers and divers alike to explore these materials and see how evidence and expertise guide every article we publish.

Boström-Einarsson, L., Babcock, R. C., Bayraktarov, E., Ceccarelli, D., Cook, N., Ferse, S. C. A., Hancock, B., Harrison, P., Hein, M., Shaver, E., Smith, A., Suggett, D., Stewart-Sinclair, P. J., Vardi, T., & McAfee, D. (2020). Coral restoration: A systematic review of current methods, successes, failures and future directions. PLOS ONE, 15(1), Article e0226631. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226631

Campbell, A. H., Marzinelli, E. M., Vergés, A., Coleman, M. A., & Steinberg, P. D. (2014). Towards restoration of missing underwater forests. PLOS ONE, 9(1), Article e84106. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084106

Danovaro, R., Aronson, J., Bianchelli, S., Boström, C., Chen, W., Cimino, R., Corinaldesi, C., Cortina-Segarra, J., D’Ambrosio, P., Gambi, C., Garrabou, J., Giorgetti, A., Grehan, A., Hannachi, A., Mangialajo, L., Morato, T., Orfanidis, S., Papadopoulou, N., Ramirez-Llodra, E., Smith, C. J., … Fraschetti, S. (2025). Assessing the success of marine ecosystem restoration using meta-analysis. Nature Communications, 16(1), 3062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57254-2

Operation Crayweed. (n.d.). Operation Crayweed: Restoring Sydney’s underwater forests. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://www.operationcrayweed.com/

Suggett, D. J., Guest, J., Camp, E. F., Edwards, A., Goergen, L., Hein, M., Humanes, A., Levy, J. S., Montoya-Maya, P. H., Smith, D. J., Sweet, M., Latijnhouwers, K. R. W., Clients, C., Howlett, L., & van Oppen, M. J. H. (2024). Restoration as a meaningful aid to ecological recovery of coral reefs. npj Ocean Sustainability, 3, Article 20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44183-024-00056-8

Unsworth, R. K. F., Sweet, M., Govers, L. L., von der Heyden, S., Vergés, A., Friess, D. A., Jones, B. L. H., Monfared, M. A. A., Steinfurth, R. C., Fariñas-Franco, J. M., Cullen-Unsworth, L. C., Banke, T. L., Tomas, F., Lusk, B. W., Mendzil, A. F., Debney, A. J., Sanderson, W. G., Thomsen, E., Preston, J., Lacey, E. A., Boerder, K., Walton, R., Vadi, T., Brand, J., & Paul, M. (2025). Rethinking marine restoration permitting to urgently advance efforts. Cell Reports Sustainability, 2, Article 100526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsus.2025.100526

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2025, February 5). U.S. coral reefs. https://www.epa.gov/coral-reefs/us-coral-reefs

Vergés, A., Campbell, A. H., Wood, G., Kajlich, L., Eger, A. M., Cruz, D., Langley, M., Bolton, D., Coleman, M. A., Turpin, J., Mamo, L. T., Steinberg, P. D., & Marzinelli, E. M. (2020). Operation Crayweed: Ecological and sociocultural aspects of restoring Sydney’s underwater forests. Ecological Management & Restoration, 21(2), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/emr.12413

Waltham, N. J., Alcott, C., Barbeau, M. A., Cebrian, J., Connolly, R. M., Deegan, L. A., Dodds, K., Gilby, B. L., Kibler, K., Maher, D., McLuckie, C., Pahl, J., Risse, L. M., Simenstad, C. A., Smith, J. A. M., Sparks, E. L., Staver, L. W., Suits, L., Wallingford, P., & Ziegler, S. L. (2025). Success of coastal habitat restoration assessed from a global dataset. Nature Communications, 16, Article 2179. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56885-3

European Commission. (n.d.). EU Nature Restoration Law. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/nature-restoration-law_en

Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (NOAA). (n.d.). Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://floridakeys.noaa.gov/

Mission: Iconic Reefs. (n.d.). Home – Mission: Iconic Reefs. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://www.iconicreefs.noaa.gov/

Project Seagrass. (n.d.). Homepage – Project Seagrass. Swansea University. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://www.projectseagrass.org/

United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. (2022). Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://www.cbd.int/gbf/

United Nations. (n.d.). Vision 2030. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

ScienceDirect. (n.d.). Coral restoration in the Philippines: Interactions with key coastal sectors. Retrieved October 12, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352485523000192